Customer Services

Copyright © 2025 Desertcart Holdings Limited

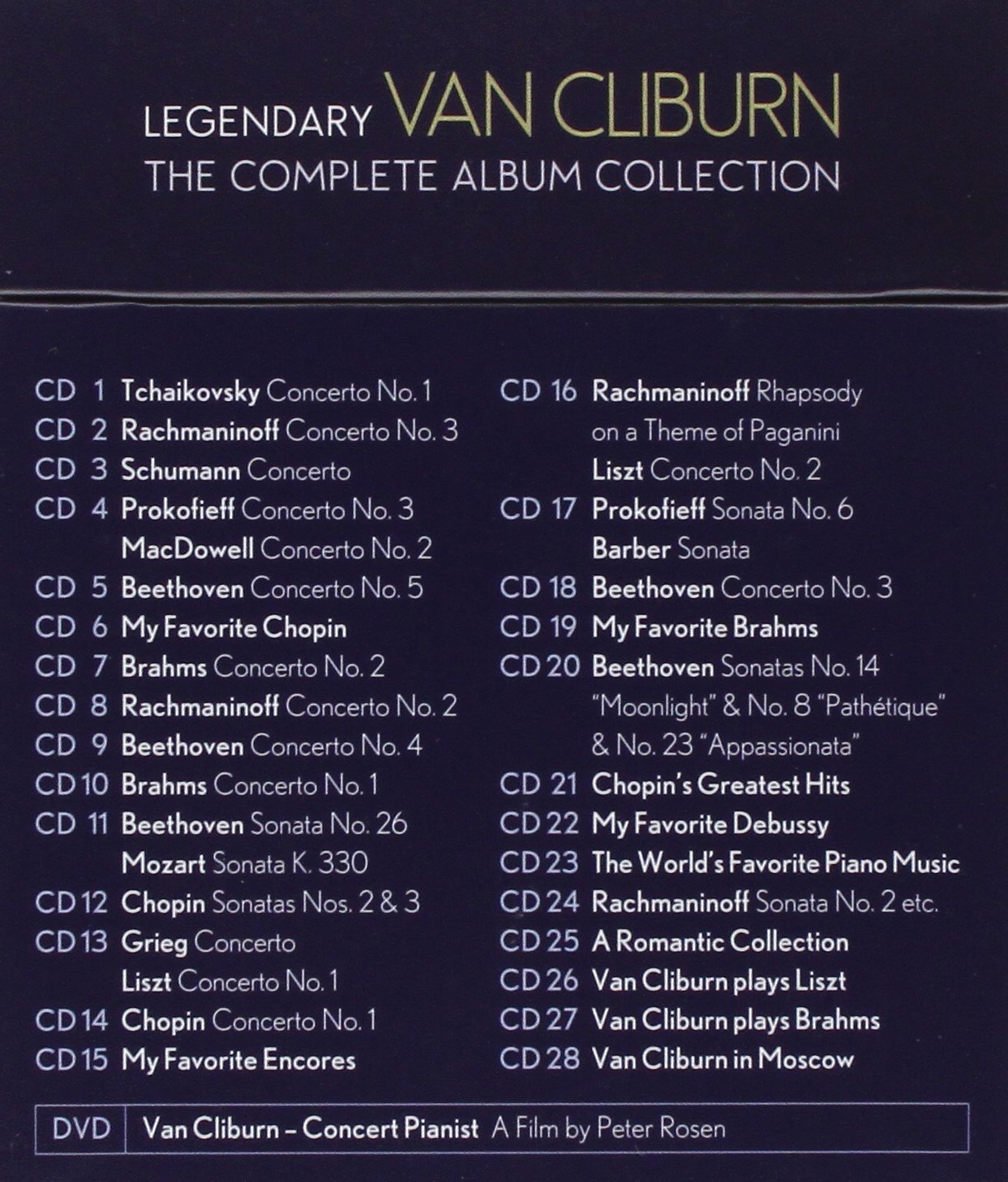

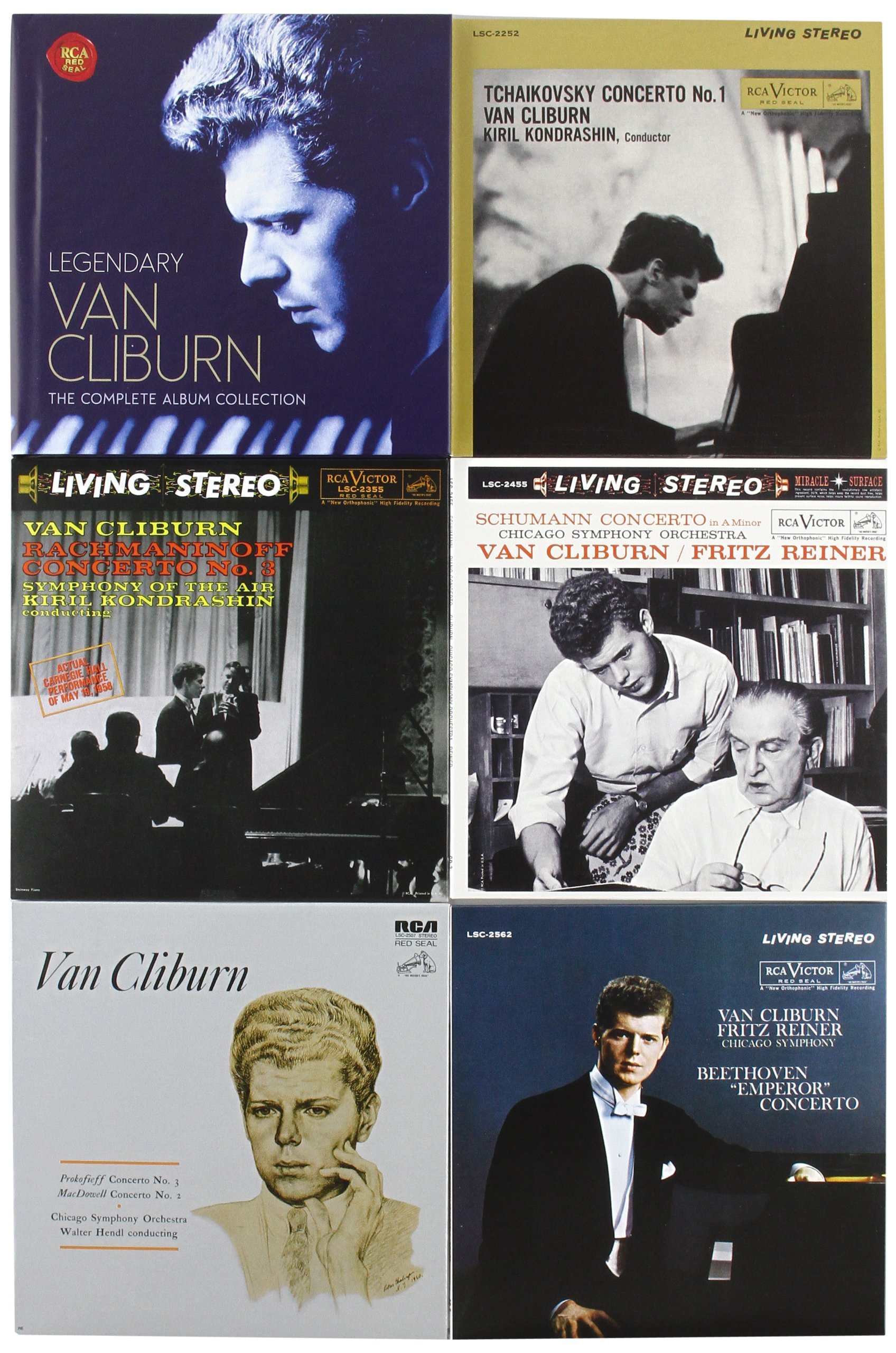

Considered to be one of the greatest pianists of the 20th century, Harvey Lavan ‘Van’ Cliburn (b. 1934) came from a musical family: his mother was an accomplished concert pianist who had studied in New York with Arthur Friedheim (Franz Liszt’s personal & musical secretary). Cliburn studied at Juilliard with Rosina Lhévinne who trained him in the Russian Romantic style and soon everyone became aware of his extraordinary talent. A jury made up of such stars as Nadia Reisenberg, Rudolf Serkin, Dimitri Mitropoulos, Leonard Bernstein, Eugene Istomin & George Szell bestowed the annual Leventritt Foundation Award upon him when he was just 20. This victory led to immediate engagements as a soloist with leading American orchestras. Cliburn was encouraged to apply for the USSR’s First International Tchaikovsky Competition, established in 1958 to showcase the country’s greatest talent. The Russian audiences fell in love with Cliburn’s playing and quickly embraced his open, authentic personality. He won the competition at the age of 23 at the height of the Cold War and returned to America a hero, complete with a ticker-tape parade in New York City, overnight superstar status and a RCA Victor recording contract. Naturally he recorded the Tchaikovsky First and Rachmaninov Third Concertos right away and RCA asked Kyrill Kondrashin to accompany him. It is to Cliburn’s credit that he sought out recordings with prominent conductors of his era that also were under contract to RCA Victor. In 1962, the Van Cliburn International Piano Competition was founded. The Van Cliburn Album Collection brings together for the first time all the live and studio recordings the legendary pianist made for RCA, from his 1958 debut recordings of Tchaikovsky's Piano Concerto No. 1 and Rachmaninov's No

R**R

So how good a pianist was Cliburn?

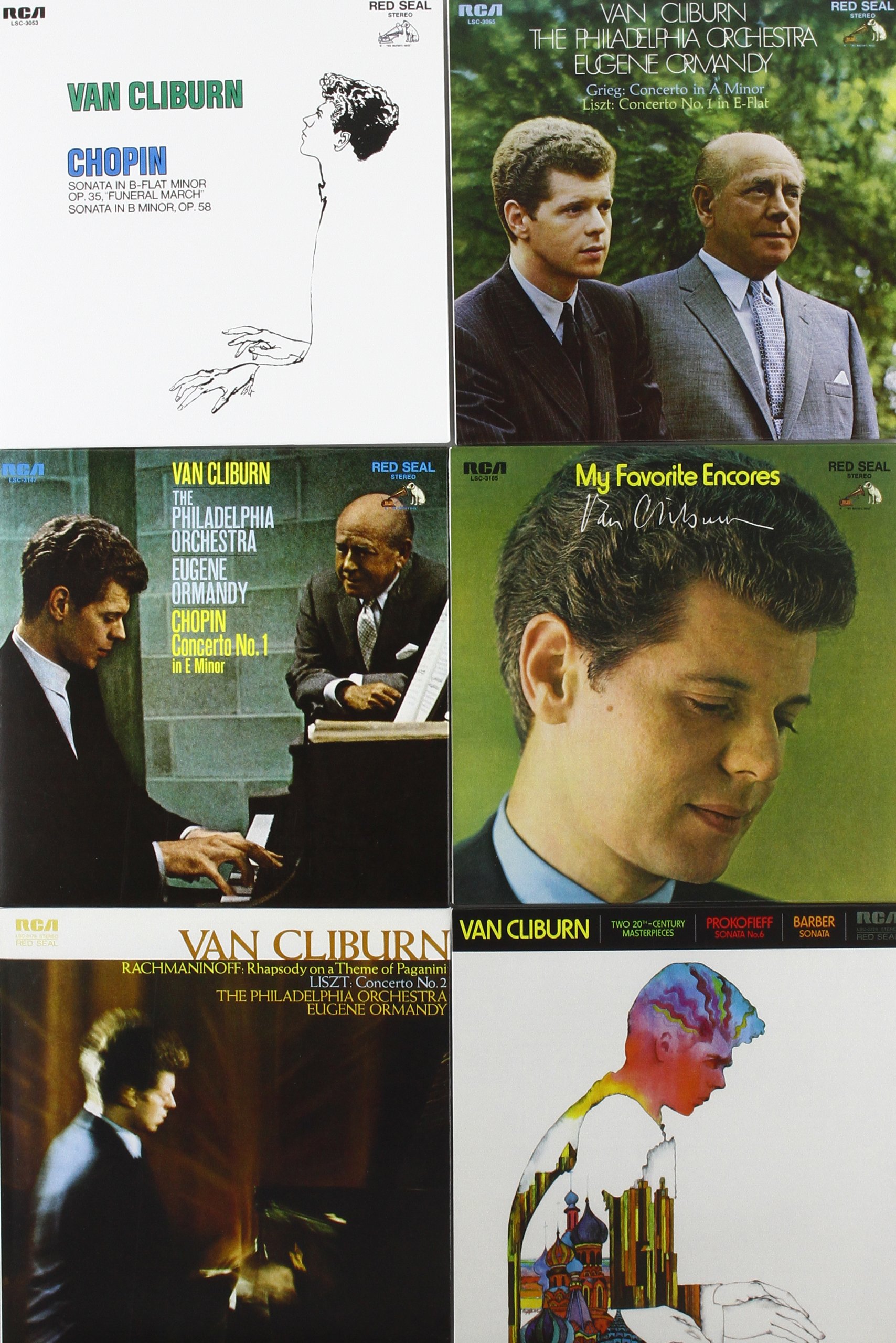

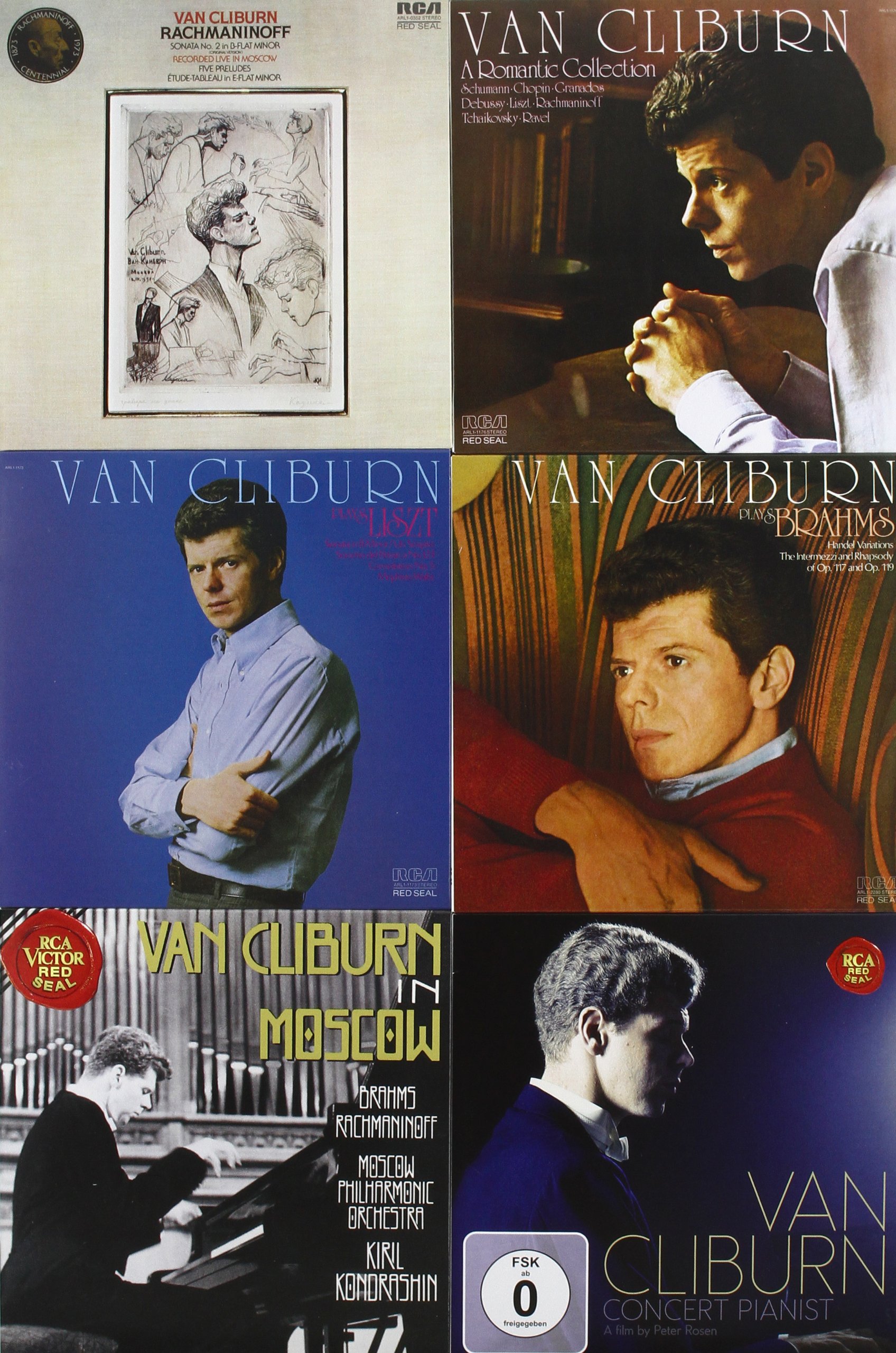

The short answer is very good indeed. The full answer takes a little longer.Like many veteran listeners I never took Van Cliburn seriously. I mean all that publicity, the competition, his rather pretentious, "cultivated" speaking style, etc. The critics weren't very positive about him either. As a result, the vast majority of these recordings are new to me. But now that all of his recordings have been reissued it's time for an assessment. So here goes.It's not accurate to say that Cliburn's recordings are paricularly uneven. Cliburn was a remarkably consistent pianist. In fact, you could say he played eveything more or less the same way (which I'll describe later). However, some works just don't respond well to the Cliburn Treatment. For example, when intimacy or atmosphere are required (as in, Clair de lune-- and in fact just about all of Debussy--Brahms' op 117/1 intermezzo, the first movement of the Moonlight Sonata) he seems wooden and ill at ease. In other cases (like the Brahms First Concerto) he plays as if the piece were by Rachmaninoff. But most of the works in this set fit him perfectly.Here are the main characteristics of Cliburn's playing.1. Tone. I've never heard any other pianist sound like this. Only Rubinstein is even close. His sound is so large and rich it just fills the entire room. It's not a matter of volume; it's the sheer amplitude of his sound. He is incapable of producing an ugly sound on the piano. Nope, couldn't do it if he tried. You might argue that sometimes (as in the first movement of the Prokofiev Sixth) an ugly sound is required. But Cliburn is Cliburn, and the movement sounds positively gorgeous in his performance. Even when he sounds disengaged (as in the Chopin First Concerto) he is a pleasure to listen to. It should also be said that Cliburn rarely plays really softly. There are very few wispy pianissimos here (rather like Rubinstein). The tone is full and rounded at all dynamic levels.2. Style. Looking around desperately for some adjective to decribe Cliburn's general approach, I came up with two: "stately" and declamatory." His playing is very "public" (hence the problem with intimate music) and totally unruffled. He plays to the upper balcony. Tempi are often somewhat slower than usual, and he rarely speeds up to create excitement. Instead, the huge sound gets even more huge, and one is overwhelmed by the sheer size and amplitude. In fact, aside from all that publicity, it's hard to understand why he so excited the public. He's not a particularly "exciting" player (which is not to say he wasn't a great one). It's the grandeur of his playing that most impresses me.3. Clarity. You want to hear each and every note of the piano part of Brahms' First? Or Rachy 3? Cliburn's your man. This clarity, combined with the steadiness of his rhythm, can sometime impart a "notey" (if such a word exists) quality to his playing. Most often, though, the clarity and stateliness makes his playing uniquely "grand." ( I wonder if the great masters of the Golden Age--Cortot or Rachmaninoff for axample--sounded like this. We'll never know from the sound on their discs.)As for the specific performances, most of them are simply superb. Of the concerto recordings, the ones with the Chicago Symphony--Beethoven 4 and 5, Prokofiev 3 and MacDowell, Schumann, Rachy 2) are all great performances. The Brahms 2 is also pretty good. The performances with Philadelphia are not nearly on this level. The Chopin 1, Grieg, Lizst, Rachy Rhapsody all sound generic to me. The Tchaikovsky (perhaps the most famous classical music recording ever issued) is excellent, but the live Rachy 3 is a mess as a recording. (I have to admit there are very few pianists--Byron Janis one one of them, Cliburn isn't another--who can make this work sound like anything but junk to me. Some highlights: The superlative Chopin Sonatas, The liszt Sonata, Brahms Handel Variations are just a few of the treasures.Cliburn generally received excellent sound, which, given the beauty of his tone, is very important. Most of these recordings are superb, paricularly the "Living Sound" recordings, which are often quite spectacular (listen, for eaxample to the Prokofiev concerto, which is breathtakingly clear and impactive). The recordings with the Philadelphia are much less impressive.These are, of course, cd "duplications" of the original lps, so recoding time is limited. I found that oddly nostalgic. At times I wanted to get up and turn the record over. Don't try to read the liner notes without a magnifying glass.Cliburn had his ups and downs, but this set makes it clear that he was a really great pianist.

H**E

A fitting tribute to America's pianist

This Complete Album Collection contains the complete recordings than Van Cliburn made as pianist for RCA, plus a documentary on DVD. It does not include his sole recording made as a conductor (issued in 1965 on a limited edition LP), nor recordings that have turned up on other labels.By the time I became aware of Van Cliburn he had already retired, and my co-workers at the Classical record store where I was employed dismissed him as a "burn out". It wasn't until some of his recordings were issued on SACD hybrid discs that I began to listen to his recordings.Despite Cliburn's All-American, apple pie loving boy from Texas image, his musical training was solidly in the Russian School. It's not for nothing that his teacher was Rosina Lhévinne, doyenne of Russian piano teachers.Listening anew to these recordings, it's also easy to see why he won the Tchaikovsky Competition in 1958. Cliburn had technique to burn, but never felt the need to get into a speed race - even when he played such warhorses as Rachmaninoff's Third Concerto. Yet it's Cliburn's recording of that concerto which brings a lump to my throat at the final statement of the third movement's "big tune." Cliburn was among the most sincere of interpreters. He didn't feel the need to drown his performances in eccentricity, yet one can instantly tell it's Cliburn performing. His temperament ran warm, but not hot like Rubinstein's and certainly not molten like Horowitz's. In many ways, Cliburn resembled Benno Moiseiwitsch, the master of relaxed virtuosity. Also, Cliburn's ringing sonority reminded many of Rosina Lhévinne's husband, Josef. (Vladimir Horowitz once remarked that he and Arthur Rubinstein together couldn't match Cliburn's tone.)Let's get one thing out of the way, Cliburn was a good musician - not a one hit wonder. There is a misconception, mostly centered in the Germanic circles, that one has to be a great Mozart and Beethoven interpreter to be a great musician. Nothing could be further from the truth. Much of this stems from Artur Schnabel's statement that he limited his repertoire to music that was "better than it could be played." There are plenty of Romantic works that are "better than they can be played". Fact is, there have been plenty of pianists who turn in fine performances of various Beethoven and Mozart works - including Cliburn for the most part. (There are also plenty of pianists who have been lauded for their Beethoven, Mozart, and Schubert interpretations for no good reason.) There are not many pianists who can hold together the Liszt Sonata, or make as strong a case as Cliburn does for the original 1913 version of Rachmaninoff's Second Sonata.As with any recorded legacy, there are high, middle, and low points. The Rachmaninoff Third Concerto, a warm, lyrical performance that proves the piece is more than a pianistic warhorse, belongs in every record collection - despite a rather lackluster accompaniment from the Symphony of the Air. Cliburn makes the best case I've heard for the heavier, chordal cadenza. The Prokofieff Sixth Sonata and Barber Sonata rank with the best - and the Brahms Handel Variations is one of my favorite versions. Many of the other recordings, including works by Chopin, Liszt, and the impressionists, rank as solid but seldom first choices - of course, the same thing could be said about the bulk of Vladimir Ashkenazy's copious output. The low point for me was the opening movement of Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata, played rather loudly and lacking in atmosphere.Cliburn was wise enough to know his limitations and be selective in the music he chose to present to the public. Chronologically and stylistically, the repertoire here starts with Mozart and ends with Barber's Piano Sonata. Cliburn didn't embrace serialism or twelve-tone because music without a "line" didn't speak to him. Nor did he play much chamber music. Instead, he concentrated on the core Romantic solo and concerto repertoire - and he played it very well.While many know-it-alls crowed over Cliburn's retirement, at least he knew when enough was enough. That can't be said for many of the intellectual crowd's pantheon of musical heroes - including Claudio Arrau and Rudolf Serkin, great artists who should have left the stage years before they did. Then there are those who shouldn't have begun in the first place.As with many of their recent reissues, Sony has organized this set to match the original LPs - which means short playing times - and included the original cover art. A perceptive essay by Jed Distler is also included. The recordings do not sound newly remastered, but Cliburn got better sound at RCA than many of his contemporaries at that label did - everything is acceptable sonically.

Trustpilot

2 weeks ago

3 days ago